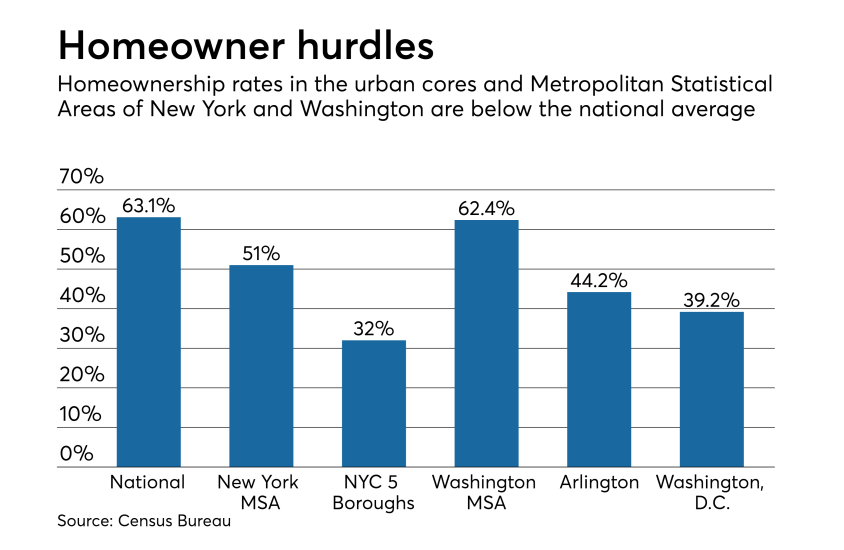

To be sure, the New York City and Washington, D.C., metro areas will see a flurry of housing and mortgage activity as a result of HQ2. But the direct benefits to mortgage lenders won't be as significant as they could've been in many of the other cities on

Here's a look at five reasons why the much-anticipated HQ2 announcement is a dud for mortgage lenders.