Special servicers used to be able to work out underperforming residential mortgages and other troubled loans quietly, with little regulatory interference.

But that was before the 2007-2008 downturn, when the market expanded for distressed assets and more large nonbank investors and servicers entered the field.

Since then, regulators have stepped up scrutiny of servicers, especially this year.

"This is turning the entire niche industry of private money lending and the nonperforming loan market into more of an industry," said Gordon Albrecht, a private mortgage market veteran. "It used to be a shadow, below-the-radar market. Now it's a front -and-center, major, major business."

Servicers cannot operate as freely as they once did, said Albrecht, a senior director at the special servicer FCI Lender Services Inc. in Anaheim, Calif.

"The private money market has come under a lot of regulatory guidelines primarily on servicing," he said. "That is the aspect of the private money business that has become much more like the institutions."

The servicing regulations that went into effect this year under the Dodd-Frank Act in particular have increased regulatory responsibilities, Albrecht said.

"You have 753 pages of Dodd-Frank servicing regulations that apply, to varying degrees, to all single-family residential one-to-four unit properties. If it's owner occupied, you've got the max. If it's not owner occupied you have fewer, but some regulations always apply," he said.

The change is a mixed blessing for servicers in the private market, according to Albrecht.

"The cost of gearing up to comply with the new regulations we didn't appreciate, but the result is that people who haven't bothered to gear up are being driven out," he said. "It was kind of the Wild West before. So the regulations have helped clean that up, and that's good."

It's a big change compared to before the downturn.

"Before the crash lenders didn't want to admit they were selling this 'scratch and dent' stuff out the back door," Albrecht said, noting that while "scratch and dent" suggests loans with a few dings, many of the loans were in much worse shape even before 2005. "These things were bad," he said. However, there were far fewer of these problem loans than there would be after the crash.

"Scratch-and-dent used to be loans that fell out of [securitization] deals," said Ed Fay, chief executive at Fay Servicing. After the downturn, they represented huge positions in deals.

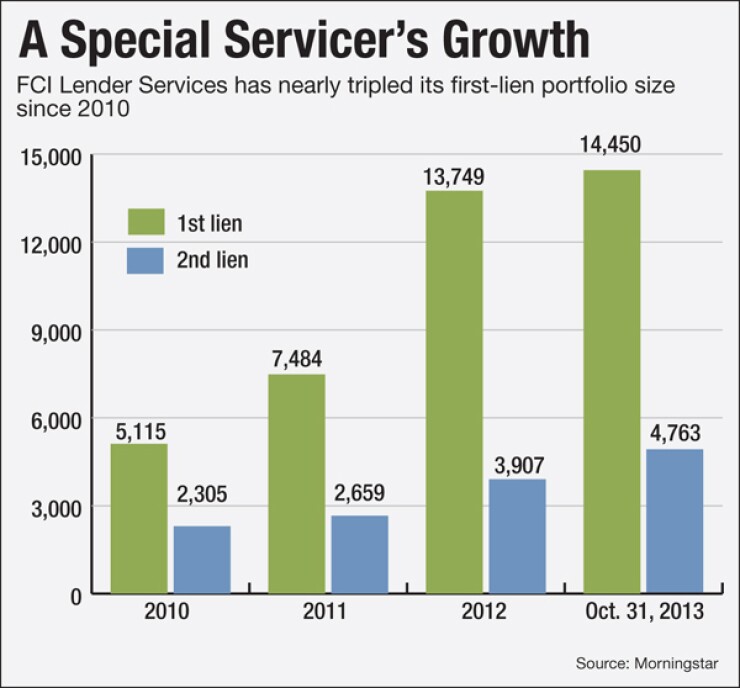

Originally, it was tough to find investors interested in troubled loans from the crash because the borrowers lacked equity. The private money market is typically skittish about leverage and won't lend on a property if the loan-to-value ratio is more than 65%. That changed around 2010, when home values started to recover, said Albrecht. Between 2009 and today, FCI's loans under management have grown to more than $3 billion from $1 billion.

Growth in problem loan volumes resulted in a two-tier market where large players that could handle the bulk initially bought problem loans, but then split the portfolios up to sell to smaller players, he said.

As the market grew, participants formed a trade association called the American Association of Private Lenders. Then they created investor-to-investor online exchanges for notes. These had mixed success, many folding. Albrecht helped form one that operates separately from the servicing business and survives today.

Private lenders who would serve the needs of borrowers shut out by the contraction in lending guidelines after the crash originally dominated the association. But it has developed more of an investor focus in the past year, Albrecht said.

Control of the group is roughly split between lenders or brokers originating private loans and investors who purchase nonperforming loans. Vendors are also members. About 90% of FCI's loans are in some manner real estate-secured and many are residential, but the mix also includes other assets.

Private money investors today demand compliant servicers because of new liability they have for their vendors' actions, said Albrecht.

"The person buying the note is responsible for verifying the compliance of all of their vendors, which means the servicer. Historically that was not the case at all. The lender was totally passive. He didn't have any responsibilities hardly at all; he just put the money up," he said.

Regulations called for better treatment of borrowers, but even if they didn't there are financial incentives in the non-securitized private money market to be considerate of a consumer who has a nonperforming or underperforming loan, Albrecht said.

"Borrower cooperation, that's No. 1. If you've got borrower cooperation, you can do something that benefits everyone. If the doggone thing is abandoned, all you're doing is trying to get the property and fix it up before it gets condemned," he said.

Private money investors' edge over the institutional market in this respect is that they bought loans at deep discounts. Thus they can quickly offer non-securitized borrowers advantageous modifications - including principal reductions - and still make money. Other lenders and investors that don't have such wide margins on their loans or might even be operating at a loss, in contrast, may negotiate fiercely with borrowers to preserve as much value as they can. While such mainstream players are averse to tools like principal reduction which make payments affordable but erode loan cash flows, private discount buyers offer them freely, Albrecht said.

"It's easier to modify because you're not dealing with all the requirements of government programs," said Robert Shiller, a senior vice president at special servicer Wingspan Portfolio Advisors (not the Yale economist).