LOS ANGELES — With the addition of new state measures recently signed into law, California and its cities may take on more than $7 billion in new debt to tackle the state’s housing crisis.

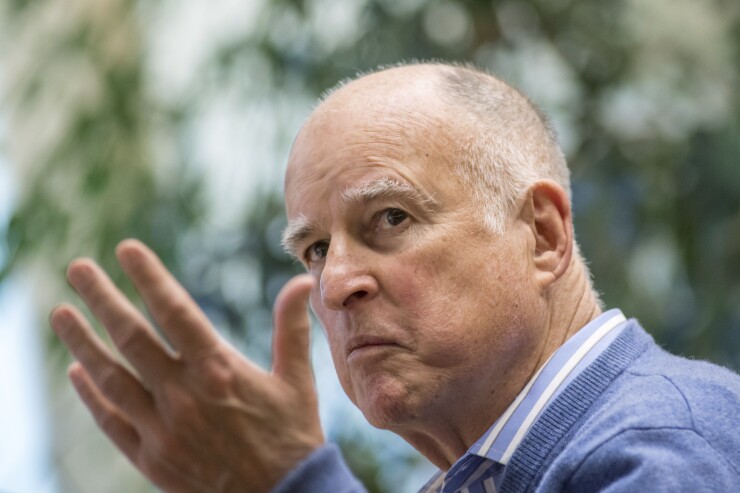

And that will not be enough, Gov. Jerry Brown said Sept. 29 when he signed 15

“Today, you can be sure, we got 15 good bills. Yes, they are good. They move the ball forward,” Brown said at the signing ceremony in San Francisco. “Have they ended the need for further legislation? Unfortunately, not.”

Two of the measures will raise money for affordable housing: one places a $4 billion general obligation housing bond measure on the statewide ballot in November 2018, while the other is expected to bring in $250 million a year through a $75 fee to most real estate transaction documents, except on the purchase or sale of property.

Senator Toni Atkins. D-San Diego, who authored Senate Bill 2, which establishes the $75 fee, called the multi-faceted package of housing a “good start” toward restoring stability.

The fee funds a subsidy to help provide housing so that working people will be able to remain in California, Atkins said.

“We know what solves homelessness: homes,” Atkins said.

Between the $4 billion on the state's 2018 ballot, and the $3.3 billion in 2016 housing bond measures approved by voters in Oakland, Los Angeles, Alameda County and Santa Clara County the potential $7.3 billion exceeds the $6.2 billion voters approved for housing on the state level between 1982 and 2014.

The rest of the bills Brown signed make it more difficult for cities and counties to avoid state housing mandates and streamline the development process for projects that meet zoning, prevailing wage, transit-oriented development and other requirements.

Larry Kosmont, a development and government consultant, said it remains to be seen just how much of an impact the bills will have.

"This set of laws will not result in construction of the needed 180,000 units a year," Kosmont said, adding it will likely result in the construction of about 10% of that amount.

Nor will it replace the $1 billion a year that once went to affordable housing through the 20% set-aside eradicated when the state's 400 redevelopment agencies were abolished in 2012.

Between the new state bond measures and the real estate transaction fee, California will likely have $400 million a year to dedicate to the housing crisis.

“It’s not enough, but it’s measurable for sure,” Kosmont said.

S&P Global Ratings analyst Gabriel Petek in a Sept. 21 report called the dearth of affordable housing in California an “increasingly acute problem” that “represents a structural challenge to California’s economic competitiveness by threatening to encourage a domestic outmigration of workers from the state.”

High housing costs – and related housing instability issues – increase healthcare costs for individuals and the state, decrease education outcomes, affecting individuals as well as the state’s productivity, and make it difficult for California businesses to attract and retain employees, according to a

In the last 10 years, the report says, California has built an average of 80,000 homes a year, 100,000 less than the number needed to keep up with population growth. Housing officials estimate that 1.8 million new housing units will be needed by 2025 based on Department of Finance population projections and demographic household formation data.

“Today’s population of 39 million is expected to grow to 50 million by 2050,” says the housing report. “Without intervention, much of the population increase can be expected to occur further from job centers, high-performing schools, and transit, constraining opportunity for future generations.”

The highest percentage of household growth is expected to occur in the Bay Area at 22%, Southern California with 38% and Central Valley communities with 17%. Between 2014 and 2015, roughly 25% of population growth came from migration from other states and countries; and 75% of population growth was attributable to births within California.

California also accounts for a disproportionate 22% of the country’s homeless population, according to the report.

“I give legislators credit for trying to chip away at a variety of avenues, but within the laws are inherent conflicts,” Kosmont said.

The package of bills is trying to tackle several issues simultaneously.

One is to provide housing for people in their 20s and 30s, who are moving to cities like Denver, San Antonio or Salt Lake City that have more affordable housing.

Another goal is to provide housing for the very poor in a state in which one out of five people live in poverty.

The package also includes legislation to encourage density around mass transit hubs.

Though Kosmont called the package of bills a bit schizophrenic, he concedes that the laws need to be multifaceted, because the housing crisis in California is not just one of homelessness, but also issues of affordability for middle class residents.

The irony of "affordable housing" in California is that it has become housing for the middle class, because most of the housing is out of reach for a significant number of income ranges, he said.

The $3.3 billion in affordable housing and homelessness bonds approved by four cities and/or counties will get the state closer to its goal when combined with the state's legislative package, Kosmont said.

Affordable housing in California typically requires a combination of financing that includes government subsidies at the local, state and federal level.

“What I said to my team is that it changes the trajectory of economic development in California,” Kosmont said. “It accelerates housing through a series of zoning requirements.”

Cities, which have encouraged retail and office development because of the tax revenue they generate, are now seeing housing as an economic tool, rather than a form of real estate development that pressures city services, Kosmont said.

“This could be a real game changer in how cities view economic development projects,” he said.

Affordable housing developer Jack Gardner said the funds "will replenish the state's proven affordable housing programs and jump-start many, many projects that are ready to get started and will make a real impact."