The mortgage industry is still coming to terms with the day-to-day tasks of maintaining TRID compliance. But other, broader systemic risks still loom, which, if overlooked, could significantly disrupt lenders' operations.

For instance, there may be more riding on the accuracy of initial closing cost estimates in the new Truth in Lending Act/Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act Integrated Disclosures than mortgage lenders realize.

"People can make mistakes. They can forget to put a charge on the form. Sometimes charges are manually inputted and that can lead to a disclosure with an inaccurate estimate. But if the CFPB sees a pattern or practice of these, that's when you can really get into trouble," said Richard Horn, a former Consumer Financial Protection Bureau senior counsel and special advisor who led the final TRID rule.

Overestimating's Hidden Cost

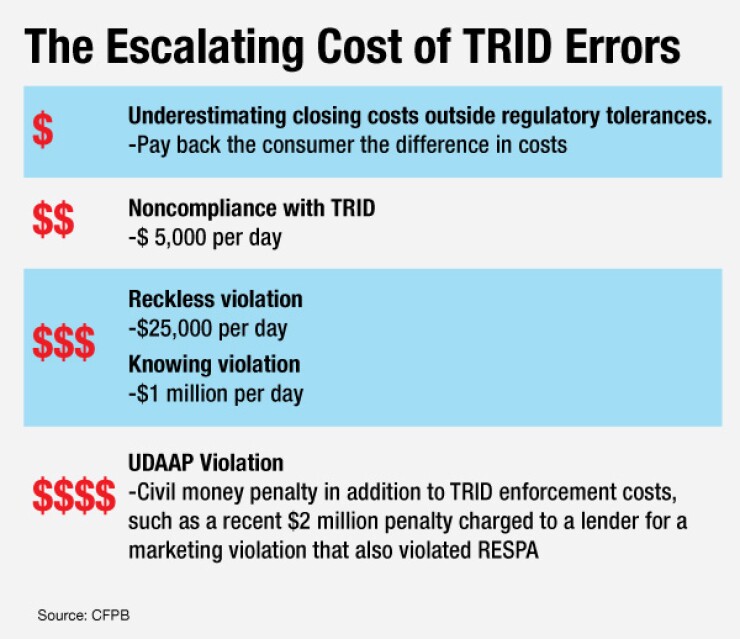

At first glance, TRID estimate deviations sound simple to remedy, assuming a lender has the funds to reimburse borrowers. If creditors lowball estimates outside specified tolerances, they have to make up the difference.

But what about highball estimates? Is competition the only deterrent?

Creditors have to make up the difference if they underestimate outside TRID tolerances, so some originators have considered overestimating their fees. But there are hidden drawbacks to this strategy.

In addition to raising costs for consumers and raising the risk of being out-priced by competitors, estimating not based on "the best information reasonably available at the time" could lead to a

Creditors that under- or over-estimate at all can face additional and significant monetary penalties for violating TRID, especially if they can't prove their estimates were based on the best information available at the time. Habitual violations can further multiply penalties drastically.

The CFPB can inflict an escalating series of per-day

And creditors over- or under-estimating on a regular basis could additionally find themselves in violation of the prohibition on Unfair, Deceptive or Abusive Acts and Practices in the Dodd-Frank Act, which the bureau enforces, said Ben Olson, a former CFPB attorney who helped craft the TRID regulation.

"The TRID rule does prohibit habitual over or under-estimating, but conduct that violates a specific rule like that can also be treated as violating other legal requirements, such as the more general prohibition on deceptive acts and practices," said Olson, who is now a partner at Buckley Sandler.

The Worry About UDAAP

A recent CFPB release of

And that's a concern because the CFPB has more leeway when it comes to enforcement actions associated with UDAAP than with technical violations, said Horn, who is now a private attorney at Richard Horn Legal PLLC.

The CFPB has "more flexibility with the damages and the civil money penalties when they add a UDAAP claim," Horn said.

The bureau earlier this year in an enforcement action found a lender's conduct not only violated RESPA Section 8 but also that it

And lenders thinking of getting another party to pay the difference on an underestimated cost should be aware of pre-existing RESPA Section 8 rules that set parameters for this, according to CFPB spokesman Samuel Gilford.

"If the creditor requires someone, or someone agrees, to pay for the creditor's tolerance cures in exchange for the referral of settlement service business, they would be in violation of

Wholesale Liabilities

TRID is

So creditors are the ones have to make up the difference if any party underestimates outside TRID tolerances.

This makes it sound like TRID can be tough on wholesalers, but it's also a challenge for brokers who want to do their best to work within the rules in order to avoid burning bridges with their business partners.

Another key TRID concern for brokers is how they should shop a loan after a formal wholesaler rejection.

"That is a hot-button issue," said John Levonick, chief compliance counsel at Opus Capital Markets Consultants. "The wholesale market has been really pushing around different ways to approach this."

The concern is related to the new TRID's deadline for an initial estimate of closing costs. The Loan Estimate must be issued within 72 hours of getting enough information for a loan application.

"The challenge is, in the event that the disclosures are issued with the intent to deliver the asset to a particular wholesale lender and the wholesale lender does not accept that loan, the broker has that residual time period to find a creditor to accept that loan," said Levonick.

The disclosure can be revised, but the

"The bureau is very clear that they don't want the originators intentionally falling short of application," Levonick said.

The CFPB did consider making the timeframe for broker transactions longer by basing it on creditor receipt rather than consumer receipt of the LE, but ultimately decided this was problematic.

"Such a distinction would disadvantage consumers who work with mortgage brokers because compared to consumers who submit mortgage applications directly to creditors, consumers who submit mortgage applications to mortgage brokers would wait longer to receive a Loan Estimate," the CFPB said.

In addition to being concerned about timing, brokers are concerned that if they draw up the disclosure and then later shop a rejected loan to a new wholesaler, it might be tough for the new lender to issue a closing disclosure within allowable tolerances. Wholesalers may or may not allow a broker to issue the disclosures.

Wholesalers' advice to brokers when it comes to TRID compliance concerns is to know their lenders well and place loans quickly and optimally, avoiding potential rejection and disclosure revisions as much as possible.

"You have to know which lender you're going to be quoting your fees off of, because if you disclose the fees incorrectly, there is no tolerance for that," said Mat Ishbia, chief executive of United Wholesale Mortgage. "In all the channels, you've got to get your stuff right up front."

This could lead brokers to restrict the number of lender partners they work with.

"I think brokers are going to work with a handful of creditors to create more predictability and have stronger relationships," Levonick said. "It creates more accountability and responsibility for the broker but also, in my opinion, it is driving brokers toward a more captive relationship."

Brokers might think about leaving the business because of this, said Levonick.

"It's possible that some brokers see that this as no longer a tenable or a viable business platform because it's so much effort to take a scenario and shop it around for the margin that they're getting currently," said Levonick.

But the wholesalers who are ultimately responsible for TRID compliance said they are doing everything necessary to help brokers navigate the rule.

TRID not only makes brokers more beholden to wholesalers, it makes wholesalers more beholden to brokers, said Al Crisanty, vice president and director of wholesale lending at Michigan Mutual.

"We are going to be closer to them than ever," he said.

TRID is challenging but it won't stop brokers, said John Councilman, president of the National Association of Mortgage Brokers and AMC Mortgage Corp.

"When consumers go to a broker it's a little different than when they go out to various lenders and shop, and I don't think TRID takes that into consideration," he said. "But everything in life is just a little more complicated because we're working with more than one lender. We will survive."