As this article was prepared, Fannie Mae 2.5% MBS were trading around 81 cents on the dollar of face value, a startling reminder of

"As recently as three weeks ago, most Federal Reserve officials said they still viewed high inflation as an ongoing threat that could merit additional interest rate increases,"

Higher for longer is bad news for housing, but rising home prices suggest that rates are not nearly high enough to cool consumer demand. The average mortgage rate

Trouble is, the Freddie data is more than a month old and the market has moved half a point since June. In the forward interest rate market known as TBAs, Fannie Mae 6.5% MBS were trading around 100/28 as this tome was written. In the secondary market, Fannie MBS are trading at yields closer to 5%, showing just how tight collateral is in the "

Regardless of which TBA contract a lender picks to sell the loan, you lose money on the trade because of the inverted Treasury yield curve. And since you are paying SOFR (5.3%) +2% for funding, or say 7.5%, you lose money on the carry too. The far contract is trading above the spot market. Thankfully, the average mortgage bank "only" lost $500 per loan in Q2 2023, according to the MBA.

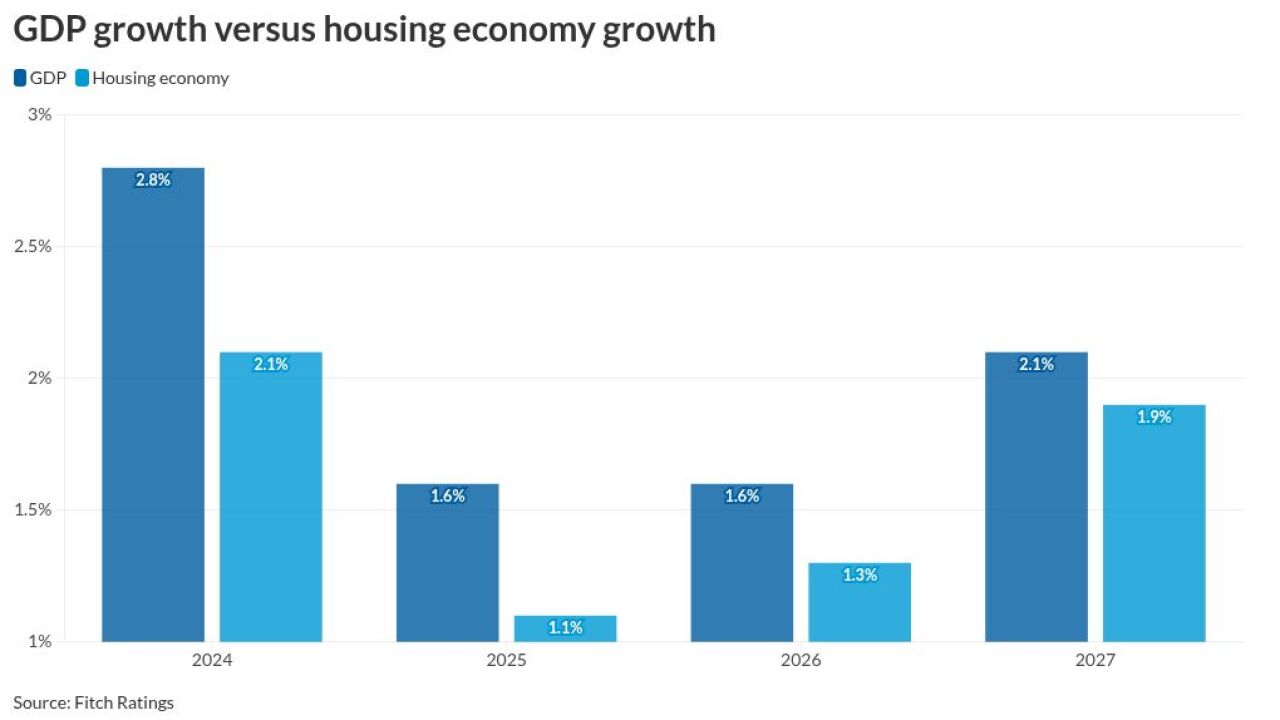

Mortgage professionals face a scary event horizon in 2024. The FOMC is raising short-term interest rates, but refuses to drain liquidity by selling bonds. This means that demand-driven inflation will continue to be a problem in the U.S. economy until we somehow work through trillions of excess liquidity provided, you guessed it, by the FOMC.

The world of financing residential mortgages is a blissful consideration, however, compared to the commercial loan market. Residential mortgages have government guarantees against default and a market subsidized by the GSEs. But across the room, banks are in full retreat from anything associated with commercial real estate. Some lenders have even reinstated an ancient practice of requiring a cash deposit at the bank before a new commercial loan is funded.

The largest players in the world of buying commercial real estate loans, from REITs to giant private equity firms and asset managers,

The chief problem facing commercial real estate is that collateral values are falling so fast that underwriters and auditors are unable to render opinions. The 47-story One North LaSalle in Chicago was just reappraised at $37 million,

The entire secondary market for commercial mortgage loans, known as CMBS, is essentially closed to most issuers until valuations stabilize. In a market that has relied upon seamless refinancing of assets at ever higher valuations for decades, the end of refinancing from banks or bond investors is a catastrophe. Funds and loan underwriters are migrating from buying loans to restructuring busted properties.

There is an extraordinary dichotomy at work, where net loss rates for prime 1-4 family mortgages are still near zero, but loss given default for bank-owned multifamily properties are back above pre-Covid levels. The Fed sees that prices for residential homes continue to rise despite the increase in short-term interest rates, but the credit environment facing some – but not all – commercial properties is far more serious.

The

"The office sector has fared significantly worse than average, with prices down circa 30% from their highs. Lodging has held up best; prices are within 5% of peak levels," notes Rothemund. If we compare the Green Street index with the current market discount for say Ginnie Mae 3% MBS, the price declines are comparable. But, again, Uncle Sam does not guarantee commercial real estate loans.

If all of this good news were not enough for one day, federal bank regulators are preparing to cut the economic returns banks earn on residential mortgage loans in half. Whereas before Covid, banks could reliably earn equity returns in the high teens, the new Basel proposal makes home lending a break-even prospect. Lending to communities of color and other low income groups will be impossible.

Penalties for high LTV loans make the new Basel capital rule proposed by the Biden White House appear to be explicitly unfair. The internal view of several large banks is that Basel capital rule means that

Independent mortgage banks will see their share of lending and servicing increase further. Commercial banks will effectively be forced out of all government lending, including VA and USDA.

Ironically enough, the increases to the capital charge for residential mortgages will probably mean that banks will be sellers of mortgage servicing assets, but they may instead shift to providing credit to IMBs in areas like warehouse and gestation. We may even see the likes of Wells Fargo remain in the commercial mortgage business even as they exit correspondent lending, perhaps including loans against MSRs.

Another group of nonbanks that may benefit from the disruption caused by the Basel capital proposal are broker-dealers, who may be able to take market share away from banks in areas like gestation finance, a fancy name for a repurchase transaction of dry whole loans that have been insured by the GSEs or FHA/VA/USDA, and are eligible for pooling into MBS.

Dealers have far lower capital charges for financing eligible mortgage collateral than do banks, making the prospect of the Basel capital rule a big opportunity for the likes of Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Barclays and the several dozen smaller dealers that trade TBAs and provide financing for small and mid-sized mortgage firms. This writer works with JVB Financial, a mid-sized dealer in New York.

Banks must continue to support the mortgage market, especially in areas such as default advances and loan buyouts, as this writer noted in a recent blog post ("