- Key insight: Economists see validity in Fed Gov. Miran's argument that shelter inflation is coming down, but note the impact to overall inflation may vary in significance.

- Expert quote: "I don't think that rental disinflation is really going to be enough of a reason on its own to say 'mission accomplished on inflation.' I think we still have a lot of inflation signals to worry about." — Daryl Fairweather, chief economist at Redfin.

- What's at stake: Fed Gov. Miran has been pushing for the central bank to be more "forward-looking" when it comes to setting monetary policy, specifically arguing that inflation will come down in the near future, which warrants cuts to short-term interest rates.

Since joining the Federal Reserve Board in September, Fed Gov. Stephen Miran has been pitching an alternative reading of the state of the economy and remedy for what ails it: much lower interest rates. This puts him at odds with Chair Jerome Powell as well as most of his fellow central bank governors.

Miran has argued in myriad speeches, appearances and interviews over the last eight weeks that inflation is on a downward trajectory, driven in part by disinflation in the housing market. In a number of his appearances, Miran has pointed to two key factors contributing to the trend: declining rental costs and Trump-era immigration policies.

The claims, however, have left economists skeptical.

While some agree that rental and housing costs are showing signs of gradual easing and may lead to disinflation in the long term, Miran's argument that reduced immigration will further cool housing inflation has faced strong pushback.

Economists also note that changes in the housing sector are unlikely to drive a sharp drop in overall inflation. Tariffs, they say, remain a more immediate concern for price pressures.

Miran has repeatedly emphasized that the central bank should take a "forward-looking" approach to monetary policy — one that accounts for factors likely to affect its dual mandate over the longer term.

The Fed governor, appointed by President Trump and on a leave of absence from his prior post as chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, argues that official inflation data often lags behind real-time market trends, suggesting that the government may be too slow to react to fast-moving developments in the market.

One trend Miran said the Fed is overlooking is the deflationary pressure from declining immigration and the deportation of immigrants already living in the U.S. He said the

In an appearance at University of Cambridge in mid-November, Miran admitted that his view regarding housing disinflation and its impact could be flawed.

"I'm always looking for where I could be wrong," he said. "I've identified this as if I'm going to be wrong ... it's probably this. I'm very focused on observing what's happening in the housing markets, and thus far, I don't see anything that tells me that I'm wrong in the U.S."

Disinflation in the housing space

Economists say there are signs that both the multi‑ and single‑family housing markets are cooling, though the effect on overall inflation will likely be modest.

Mike Fratantoni, chief economist at the Mortgage Bankers Association, said that on a national level, asking rents "are flat to declining," but he stressed the shift will appear in the economy "over time."

"There are certainly markets where because of an oversupply in the apartment sector, you're seeing rents decline in a more noticeable way," Fratantoni said. "We are also seeing the rate of home price growth slow. Our own forecast actually has [home price growth] falling … and getting negative as we go into 2026 and 2027."

Fratantoni said he agrees "with the overall premise" that a reduction in housing costs, whether it be homeownership or rent, will put some downward pressure on inflation measures over a multiyear period, but added that he expects inflation to spike in the near-term.

"The only place where we're seeing a little bit differently from Governor Miran is that I think we're going to see inflation pick up over the next six months or so before these disinflationary factors really begin to weigh on the top line number," he added.

Meanwhile, Patrick Harker, former Philadelphia Fed president, brushed off the importance of housing disinflation and its impact on the economy, noting "it's an argument," but not one he adheres to.

Daryl Fairweather, chief economist at Redfin, agreed that there is a lag in how rents are measured and said it is reasonable to anticipate that the Federal Reserve's measure of inflation will fall as rents continue to decline.

However, Fairweather cautioned that lower rent costs won't necessarily brighten the overall inflation picture.

"Ironically, even if people aren't spending as much money on rent, they might end up spending more money on other items, which could lead to inflation," she said. "I don't think that rental disinflation is really going to be enough of a reason on its own to say 'mission accomplished on inflation.' I think we still have a lot of inflation signals to worry about."

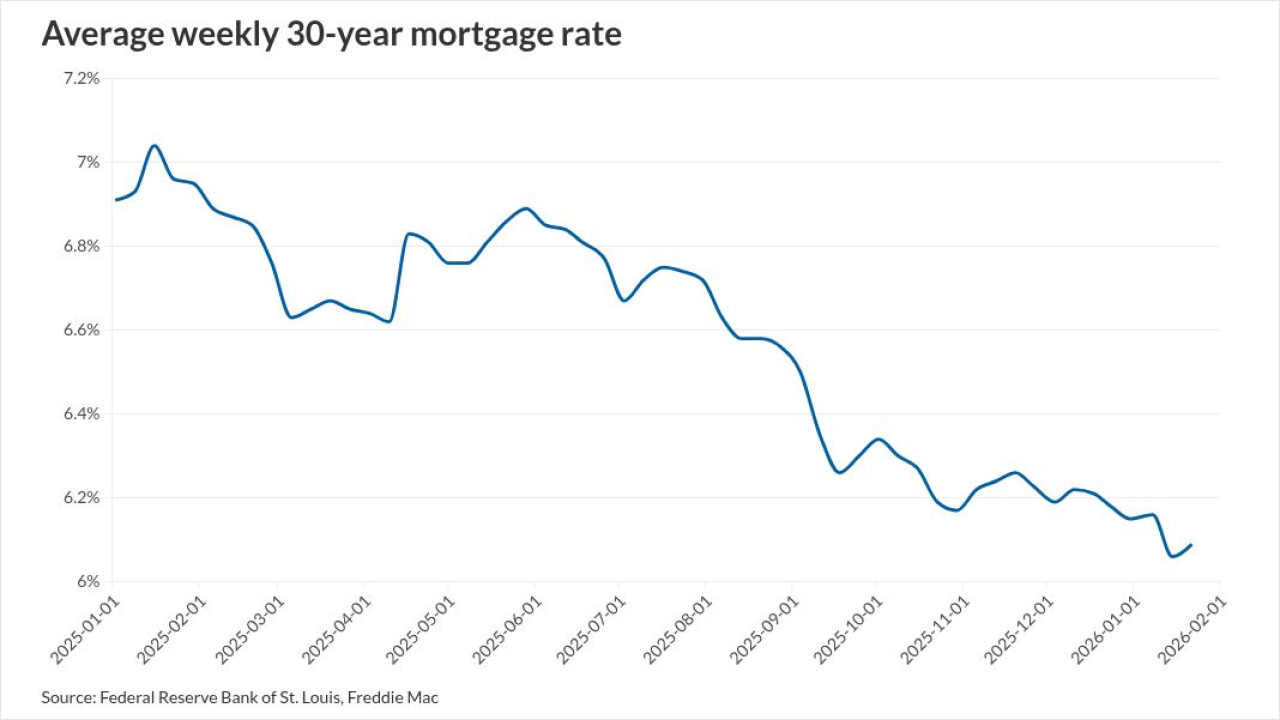

Over the past year, asking rents

Impact of immigration policies

Miran in a speech at the

Some economists interviewed don't see validity in these claims.

"I think the claims are madness," said Rodney Ramcharan, professor of finance and business economics at University of Southern California and a former Fed economist.

"This is based on a middle school level of economics," said Exequiel "Zeke" Hernandez, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Business.

Despite signs appearing that over time rental costs will level off, most economists were skeptical that current border policies will play a noticeable role in bringing down inflation, with some even saying immigration policies could have the opposite effect.

"If rents are coming down, they're coming down because the housing market is weakening," Ramcharan said. "You have to trade off that immigration keeps our wages low, so if you don't let folks come in, you're going to push up wages."

Hernandez echoed similar sentiments, noting that reductions in net migration can cause economic depressions in local communities and create inflationary pressure due to the absence of inexpensive labor.

"It seems to be true that if you remove people, there's going to be fewer people demanding that housing, and the price of that housing should go down, in theory," Hernandez said. "The problem is that when you remove people, you're also depressing the economy, so it's a demand shock. There's fewer people buying stuff and it's the equivalent of creating a mini depression in the local economy."

Even so, Fratantoni does see some validity to this argument, noting that if there is a slower immigration environment there will be a drop in demand in the rental market.

"That's going to show up differently in different parts of the country where new immigrants are a larger or smaller part of rental demand, but it is going to be contributing to some of this disinflation coming from the housing sector," he said.

The tariffs in the room

Most economists interviewed agreed that even if the housing sector experiences disinflationary pressures, the Federal Reserve should be more concerned with how President Trump's tariff policies will affect inflation in the near term.

Beth Ann Bovino, chief economist at U.S. Bank, said that inflation is starting to drift further away from the 2% target of the Fed, which is something the central bank should keep an eye on.

"I am concerned about the inflation readings around 3%," she said. "Even if tariffs are a one-off, meaning it goes up and then that's a one time deal, it still has a feed through effect that lasts a while."

So far, companies have absorbed most of the tariffs on certain products. Recent data from Goldman Sachs shows

But Fratantoni warns that this will soon come to an end, which will "overwhelm" any potential drop in the shelter component of the Consumer Price Index.

"I agree with the general sense that the tariff impact is going to be relatively short-lived, but I just don't think we've seen it yet, because I think businesses have been absorbing much of that cost, and they're now saying they can't do it much longer," Fratantoni said.

John Heltman contributed to this report.