During a 2018 hearing before the House Financial Services Committee, former Federal Reserve Board Chairman Janet Yellen confessed to being "perplexed" as to "why so many

Of course, the FOMC under Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke

Early on in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the

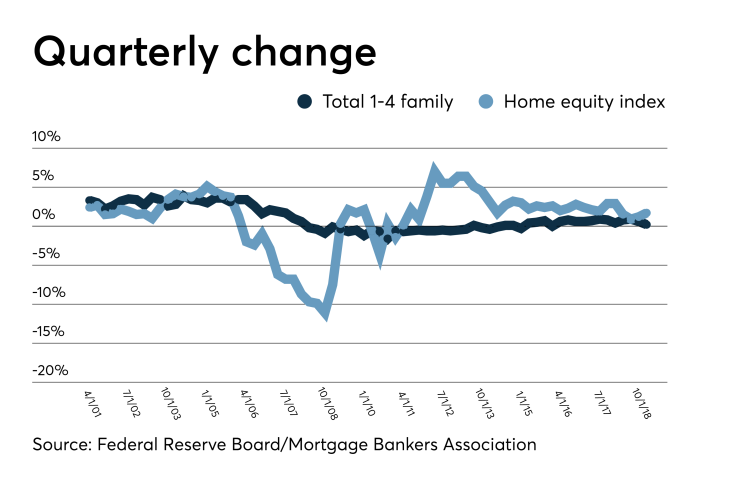

Since 2008, the equity in American homes has soared by almost $10 trillion to just over $32 trillion, according to the Federal Reserve Board. Of note, credit creation tied to mortgages declined in the 2013-2016 period and then grew at a far lower rate. As with the once trusted connection between employment and inflation, for example, the tie between interest rates and housing credit seems broken. The chart below shows the quarterly rate of change in total outstanding one-to-four family mortgages and total home equity in the U.S. since 2000.

The chart reminds us that home equity values began to slide in 2005, around the time production at lenders such as Countrywide Financial and Washington Mutual started to fall. Home lending volumes continued to rise, however, until the financial crisis in 2008, then slowly declined over a decade. The FOMC's deliberate manipulation of the bond market did have the effect of forcing up home prices in a decade long seller's market, yet mortgage lending volumes were flat to down single digits until the end of Quantitative Easing in 2015. In terms of expanding mortgage credit, Fed policy clearly failed.

When it became clear that low interest rates alone would not lead to an increase in the purchases of new or existing homes, the FOMC shifted to a secondary position, focusing instead on the increase in home prices to show that low interest rates were "helping" housing. This change in Fed posture was essentially an embrace of the "wealth effect," a discredited economic theory that says when people see increased paper wealth in stocks or even a house, they will feel richer and spend more.

Not only do the policies of the FOMC seem to have been unhelpful to expanding housing credit, but indeed QE seems to have more broadly retarded lending and hurt the economics of the home lending business. Profitability for mortgage lenders during the past decade has worsened each year, with record low or even negative secondary market results for bank loans.

Even though the U.S. economy saw record low interest rates during this period, lending by both banks and non-banks actually went down during the time of "extraordinary" policy actions under Bernanke and Yellen. The resulting competition for fewer loans killed profitability, particularly for commercial banks which are still fleeing residential lending. Sales of one-to-four family loans by banks into the secondary mortgage market have fallen 30% since 2016, according to the FDIC, this because of huge losses on one-to-four family loans and the costs imposed by the 2010 Dodd-Frank law.

In addition, changes in law and regulation have made it more capital intensive for banks to originate one-to-four family loans and related construction and development credits, adding to the long list of negative factors holding back new home construction lending by banks. The regulatory changes made since 2008 have contributed to the lack of new supply of homes even as the population of Americans looking to form households has grown apace.

The surge in home prices since 2008 and especially since 2011, when Wall Street fund managers discovered single family homes as an asset class, has been most pronounced in the largest coastal markets such as New York, Los Angeles and Seattle. "The 80th percentile renter in Los Angeles can only afford 40% of homes for sale, with a house buying power of $561,400 and an income of $103,020,"

Reduced home price affordability hurts the poor the most, especially when bank regulations encourage insured depositories to lend only to the wealthy. Banks have mostly abandoned the low-income market for FHA, VA and USDA loans and any borrower below a 700 FICO. Today bank portfolios are pristine, with average FICO scores well in excess of 700 and virtually zero net defaults. Indeed, 75% of all mortgages in the U.S. now have FICO scores above 720, illustrating how the post crisis period has seen the poorest households left out. Chairman Powell addressed the issue in December: "Researchers found that, as in many urban areas nationwide, a large portion of renters in rural communities struggle to afford their rent — a finding that will not come as a surprise in this room. Fortunately, our staff also highlighted promising policy and practice solutions that have been implemented in some communities to try to address these challenges, including the establishment of dedicated funding for affordable housing and the elimination of exclusionary land use and zoning policies."

Hopefully issues like zoning, land use and bank regulatory rules will be addressed soon to rebalance some of the excessive caution in the 2010 Dodd-Frank law with respect to housing and bank capital, especially for community banks below $10 billion in assets. But equally important is for the Federal Reserve Board to take a hard look at the impact of monetary policy on housing in the post 2008 period.

Was there really a net benefit to house and household formation due to QE and other types of market intervention? Home prices have certainly soared for a number of reasons, but the lack of supply and the surfeit of cheap fiat dollars seeking a return, any return, contributed the most to a sharp deterioration in housing affordability in the United States. Changes in the relationship between interest rates and housing may render an important traditional tool of monetary policy diminished or now possibly even counterproductive in the future.